When Serah Luka was rescued from Boko Haram captivity last week, the Nigerian army celebrated the freedom of a second schoolgirl kidnapped from Chibok two years earlier.

But after the Chibok parents support group, who campaign for the release of the 219 teenagers taken from the town in northern Nigeria in 2014, announced that Luka’s name was not on their list, everyone lost interest in her and the 96 women and children rescued alongside her from the Sambisa forest.

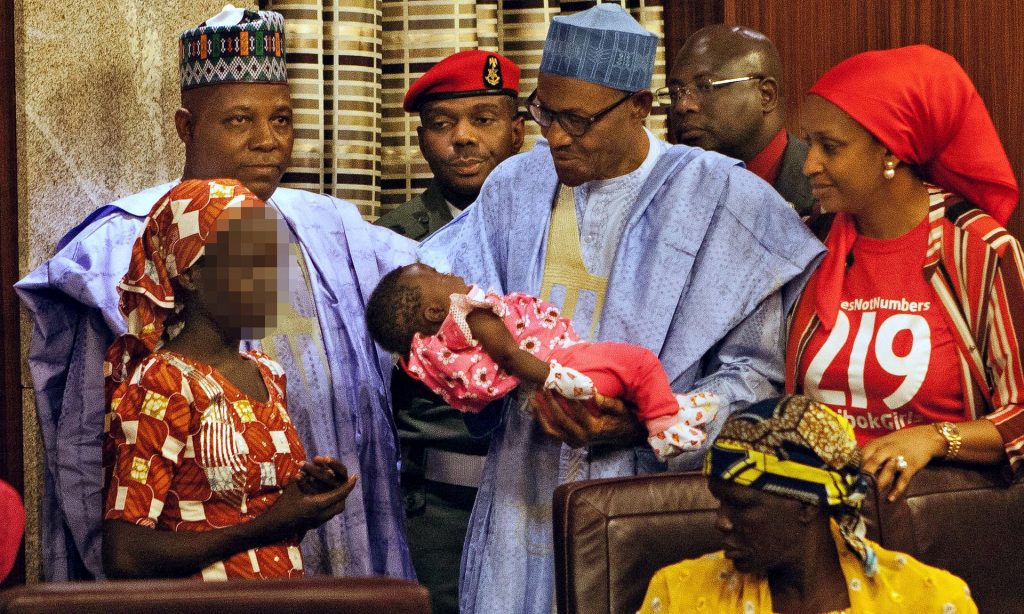

Unlike Amina Ali, a young woman found a few days earlier who was on the Chibok list, Luka was not taken to meet the president, feted by the international media or promised free schooling for life.

Buhari told Ali that the government would “ensure that she gets the best medical, emotional and whatever care that she requires to get full recovery and be integrated into the society”.

Luka received no such promises. Like thousands of Nigerian women and children who have been rescued or escaped after being kidnapped by militants, it is likely she ended up in a camp for people fleeing the insurgency.

According to local media reports, Luka had attended the same boarding school as the Chibok girls but had been kidnapped from her home in a neighbouring town on a different day. She was the wrong kind of kidnap victim.

To their credit, #BringBackOurGirls campaigners, whose movement was inspired by the Chibok kidnappings, welcomed Luka’s release, declaring in a statement that “every citizen returned is victory for us all”. But updated campaign posters reflected the number of Chibok girls still missing: 218.

Luka is not the first young woman to find that not being one of the famous Chibok students has radically altered her fate.

In September 2014, two buses filled with schoolgirls were driven into army barracks in Maiduguri, the Borno state capital. Officers thought they were the Chibok girls, and rushed to announce their rescue.

When it turned out they weren’t the actual Chibok students, things suddenly changed. The girls were reportedly moved out of the barracks and sent to camps for internally displaced people, to live in crowded and difficult conditions.

The priority given to the fate of the missing Chibok schoolgirls is a talking point in the camps in northern Nigeria, where many young women who have also been held captive by Boko Haram ask why their welfare isn’t considered as important.

“I’m equally a student,” said 17-year-old Kabiratu, who lives in a camp in Maiduguri. Kabiratu was abducted in the north-eastern town of Bama in February 2014 and made to cook for the militants during her seven months in captivity. “Maybe if I was kidnapped from school, my story would have been different,” she said.

Life in the camps is hard, with families queueing for hours for food and inadequate services for pregnant women and young children. In February aid agencies said about 450 children between one and five had died of malnutrition in 28 camps in Borno state during 2015, while 6,444 children of the same age bracket were severely malnourished.

The environment is also not safe, with reports of rape, violence and child trafficking – particularly in the unofficial camps set up to deal with overcrowding.

“The Chibok girls didn’t get [treated like] this,” said another woman in the Maidugiri camp, referring to the first set of schoolgirls who escaped from their captors not long after they were taken. “How many of us can be kidnapped from a secondary school?” she asked.

Along with the hardships, the young women in the camps face the prospect of never being able to return to school.

In February, Borno announced the reopening of state secondary schools which had been closed two years earlier because of the insurgency, relocating the 4,500 people who had taken refuge on school premises to other camps.

The news was a relief to students who have waited years to return to the classroom, but it offered no hope to the young people, particularly girls, still stuck in the camps.

Unlike those Chibok schoolgirls who managed to escape and were offered a new life and ongoing education in the US, the young women in Maiduguri camps can only hope that their fortunes will change.

“I know my time will come,” said Kabiratu. “This suffering will certainly not be forever.”