Netflix recently announced that it is teaming up with Angelina Jolie to produce and direct a film adaptation of Loung Ung’s best-selling memoir, First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers. The book offers a firsthand account of the brutality and devastation that wracked the country during the reign of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge regime. Ung hailed from a large and affluent Chinese-Cambodian family, which was torn apart by the violence. When she was only seven years old, Ung was recruited into a military training camp for child soldiers, where she learned how to fight Vietnamese forces.

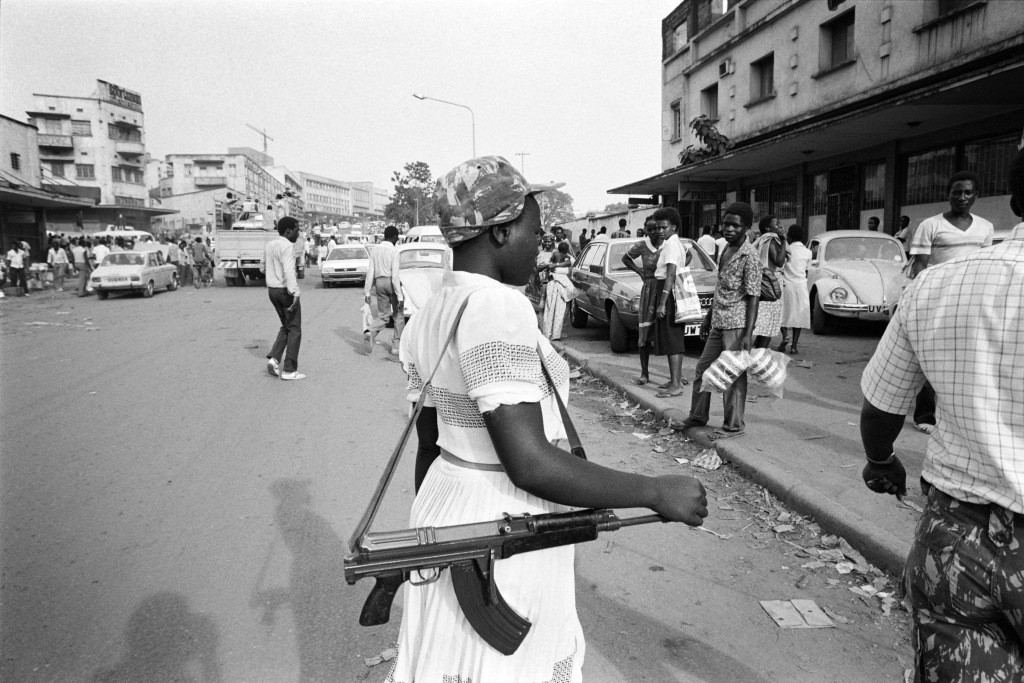

The latter details of Ung’s military experience might come as a surprise, because our perception of child soldiers tends to conform to fairly traditional gender stereotypes. We think of small boys toting big guns, and young girls reduced to the sexual playthings of abusive commanders. But this generalization diminishes the complexity of girls’ experiences within armed groups. Around 40 percent of all child soldiers are female (exact numbers are near impossible to pin down due to underreporting on this issue). While it is true that girls are often subjected to sexual slavery and relegated to “domestic” tasks—like cooking and midwifery—some female child soldiers also receive weapons training and are deployed in combat.

Many armed groups (and some government forces) operating in regions of conflict have actively sought out underage female recruits. In a paper titled Girls in Armed Forces: Moving Beyond Victimhood, Dr. Miryam Denov of McGill University writes that in certain war-torn regions of Africa, girls are particularly valued because “they are perceived as highly obedient and easily manipulated, they can swell the ranks if there is a shortage of adults, and ensure a constant pool of forced and compliant labor.” By and large, girls enter into armed groups after being forcibly abducted and torn apart from their families under extremely violent circumstances. But girls have been known to voluntarily join militias. Sometimes, they are motivated by ideology, like the many teenagers who have uprooted from Western countries to join ISIS. In other circumstances, young girls hope armed groups will provide protection from poverty, sexual abuse, forced marriages, and state or rebel-inflicted violence.

Whether or not girls are enlisted into combat depends on the region and on the nature of the militia. The jihadist group Boko Haram, for example, usually uses abducted girls as domestic workers and sex slaves. By way of contrast, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a hardline Marxist and notoriously ruthless guerrilla movement, famously treats its female members much like their male counterparts. FARC has encouraged—and forced—girl soldiers to engage in back-breaking military training and to fight on the front lines during combat (in February of this year, FARC promised to stop recruiting and kidnapping underage fighters as part of conciliatory talks with the Colombian government). But girls also fueled FARC’s agenda without fighting on the battlefield. In an article from 2013, the BBC quotes a former girl soldier as saying, “The FARC really wanted to recruit [girls] for this reason, because no one suspects a little girl. A little girl can transport money, weapons, drugs much more easily.”

Girl soldiers have been known to contribute to the functioning of military forces in a variety of ways, from carrying ammunitions, to looting goods, to participating in combat activities. But fighting alongside male soldiers rarely protects girls from sexual brutality, and their status as fighters is often negligible. Milfrid Tonheim, a researcher in administration and organization theory at Norway’s University of Bergen, spent over 20 weeks interviewing former girl soldiers in the Eastern Congo as part of a research initiative funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign affairs. She spoke to three women who belonged to the Mai-Mai militias, and who had all been deployed in combat scenarios.

“In the local militia and defense groups … there is a perception that children are purer and [as such have] magical protective powers,” Tonheim told Women in the World. “This perception has led to both girls and boys being used as bodyguards of commander[s] of these types of groups. In reality these children are living shields who protect the commanders by fighting, but also often take bullets for [them].”

Occasionally, girl soldiers can ascend the ranks of the paramilitary machine. A 2005 study notes that in Northern Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army, girls served as captains, lieutenants, and corporals. A second research paper by Miryam Denov, which surveyed 80 child soldiers of Sierra Leone’s Revolutionary United Front, found that one girl had been promoted to the rank of commander. She had been rewarded with this position after proving herself to be uniquely aggressive in looting and abducting other children. “Promotion to the rank of commander was deemed to be a pinnacle of success within the RUF,” Denov writes. “A source of privilege as well as pride, to be a commander meant being allowed to lead their own units of child combatants.”

And this is where girl soldiers’ experiences can become particularly complicated. Sometimes—though not usually—girl soldiers transform from frightened recruits to vicious fighters, emboldened by a sort of power that they would not have acquired in the patriarchal communities where they were raised.

Since the summer of 2011, photojournalist Marc Ellison has spent time on and off in Uganda, interviewing former girl soldiers of the Lord’s Resistance Army about their lives once they returned home to their communities. He compiled some of these interviews into a multimedia project called Dwog Paco—a derogatory term for returnees from the Ugandan bush. One of the young women, Alice, struggled with an acute sense of powerlessness after leaving the LRA. As Ellison reported in The Toronto Star, Alice told him: “In the bush, you can get what you want from people because you have a gun — but here I do not have a gun. In the bush, we were free to do anything we want without much control. You could ambush vehicles, you could loot.”

Ellison told Women in the World that Alice was “quite unique” in her prolonged affinity for violence: she was abducted at a very young age and thoroughly indoctrinated by the LRA. But Ellison also noted that many of his interview subjects felt tinges of regret after leaving armed groups. “A lot of the women said they were surprised, when they came back, how hard things were,” he explained. “When they come back from the bush, often they haven’t come back with their ‘husbands’ [i.e. the male soldiers they were forced to marry], often they have a couple kids to look after … Often they were stigmatized in their own community or by their own family members. Sometimes they wonder, ‘Why did I leave?’ Ugandan society is a very patriarchal society … I would say there may have been a little more gender balance in the bush than [in] Ugandan society as a whole.”

The challenges facing girl soldiers who come back home—usually after escaping, getting captured by government forces, or being released through demobilization agreements—are indeed quite steep. While conducting research in the Congo, Milfrid Tonheim found that former girl soldiers are often perceived as dangerous criminals, and stigmatized for engaging in sexual activity—albeit forced—while they belonged to an armed group. “Girls who return with children appear to have higher rates of rejection and stigmatization compared to girls returning without children,” Tonheim added. “The children are themselves stigmatized, but also constitute yet another reason to mock and stigmatize their mothers. Children of former girl soldiers are also perceived as an extra financial burden to the family where the girl lives. Quite a number of former girl soldiers in my study had experienced rejection by their biological parents when returning home.”

When combatants return from armed conflict, they are often acculturated back into civilian life through “Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration” (or DDR) programs, which are carried out by agencies like the United Nations and UNICEF. But by and large, DDR programs have not been able to successfully address girls’ complex social, psychological, and medical needs. A 2010 report by the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers found that in the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, “[t]here has been no systematic government or UN effort to reach girls and ensure their inclusion in reintegration programs.”

Securing the release of girl soldiers can be difficult because they are often concealed by military commanders as “wives” of male fighters. At other times, girls steer clear of reintegration programs in order to avoid being branded as a child soldier. As a result, many girls demobilize on their own, without any help from reintegration programs. And DDR initiatives, which are usually stretched thin due to a lack of funding, cannot always provide sufficient help to former soldiers who do go through the system. “There is a lack of help on the ground to help women with counseling,” Marc Ellison said of his observations in Uganda. “It’s hard for them to reintegrate if they are suffering from PTSD or mental trauma.”

Such are the traumas and tragedies of girl soldiers, who are often brutalized—both physically and emotionally—from the time they join an armed group until after their return home. More frequently than people realize, young girls become perpetrators of violence. But regardless of the tasks assigned to a girl soldier, she is always a victim too.

An earlier version of this article stated that Marc Ellison spent only three months in Uganda in the summer of 2011. While this did indeed mark the first phase of his research project, he has been travelling back and forth from the country since that time.